LAYLA AND MAJNUN

Layla and Majnun is a multidisciplinary collaboration between the Mark Morris Dance Group and the musicians of Yo Yo Ma’s Silkroad Ensemble, featuring the Qasimovs, masters of the indigenous Azerbaijani music Mugham. Based on a Persian narrative poem, Layla and Majnun follows a plot about star-crossed lovers, akin to that of Romeo and Juliet. Life is interpreted through the theme of love, and love remains a constant source of grief and suffering. That, which nourishes us also destroys us, ultimately taking us beyond death and suffering, into the Allegorical Realm.

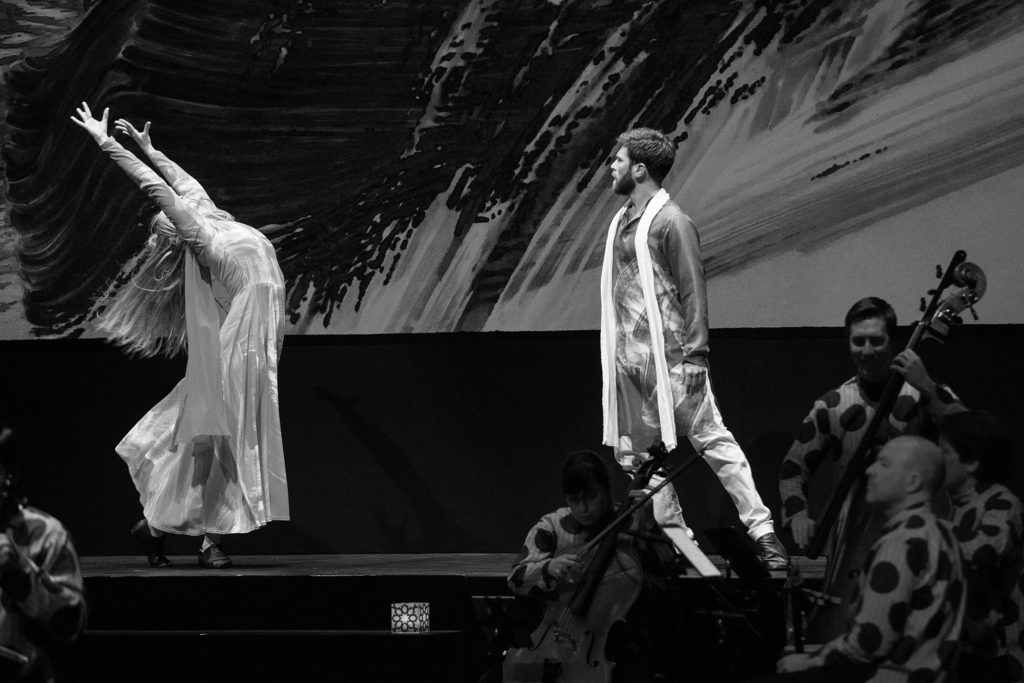

From the outset, we are presented with Morris’ signature choreographic styles; dressed in flowing robes, the dancers file across the stage, often creating almost origami-style spatial and physical configurations. Those who followed Morris’ collaborations with Yo Yo Ma playing Bach Cello Suites about 15 years ago, will immediately recognize the dramatic extensions, unions and duo work. But that was then – it was and is timelessly beautiful. It was made in response to Bach, the Titan of Western Art Music. This is now – made in response to Ma’s subtle composition and the ecstatic, weeping voices of the Qasimovs. This is now – we are presented with the tapestry of Eastern and Western instruments and, are once again, in the era of Eastern and Western dialogues, tensions, reconciliations and (mis)representations. And in the context of all of this, of the universal themes of love and grief and of the murky abyss that the Qasimovs invite us to jump over, the choreography does not deliver until the final section of the work.

For about 50 min the dance crowds and drains the breath of music. The work of the Qasimovs, in particular, is so effortless that the choreography very quickly becomes pompous in contrast to the musical aesthetic. And then, there is also the cultural aspect of work and the notion of fusion. The program notes suggest that the choreography draws on elements of ballet, contemporary and folk dance, but what is presented here rings hollow and tokenistic, particularly the spinning movements that reference dances of the whirling dervishes. It seems that Morris remained in the era of Ma’s Bach performances, but hasn’t quite moved with the times or arrived to this work.

One may try to consider this tension between the languages of movement and sound as a deliberate aesthetic ploy, but it takes a very keen and generous stretch of perception to adopt this possibility.

Towards the end, in the section titled The Lovers’ Demise something moves quite radically and dance comes into closer aesthetic proximity to the music.

The sequence of Lovers’ death and their metaphoric ascent is delivered through swift and simple movements of falling and rising. In the closing musical phrases the instrumentalists all join in song, simply humming and vocally seeing Layla and Majnun off, to the other world.

We are invited into a world of grief and dignified acceptance. Loss transforms into possibility when we transcend the current and the known reality. While jumping over the abyss, we have grown wings. It was worth this wait; we waited for a long and an awkward time for different elements of this work to align. The work comes recommended as musically brilliant and confused on its conceptual, multi-disciplinary level.

Just when we got there with the work we take one more aesthetically misaligned blow during the curtain call. The Qasimovs and the Silkroad Ensemble win us over once again, during the curtain call, with their humbleness. The dancers appear more stilted and forceful. And then, the choreographer comes on, taking half a dozen melodramatic bows. It is as though we must take him away not just in our memory, but also our blood stream and neural pathways? This certainly matches the pompous and stilted aesthetic of much of the dance.

Yes, see the work for the moments of profound beauty and musical excellence, but do your parasympathetic nervous system a favour, and leave after the Qasimovs bow.