DYBBUKS

DYBBUK (n): a malevolent wandering spirit that enters and possesses the body of a living person until exorcised. In Yiddish it comes from the word livdak which means to cling.

Chamber Made has taken an iconic old-world play (‘The Dybbuk’ 1913, Ansky) and dug under it, deep into the dark, loud and warm female subconscious. During a lengthy research and experimentation period, Samara Hersch and team probed it with questions about Leah (the possessed protagonist) and how to give rise to her transformative experience.

“Ritual recognises the potency of disorder. In the disorder of the mind, in dreams, faints and frenzies, ritual expects to find powers and truths which cannot be reached by conscious effort. Energy to command and special powers of healing come to those who can abandon rational control for a time.” – Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger (1966)

This intriguing quote is displayed in the foyer, along with a history of performances of the original text, and explanations of particular Jewish rites and traditions enacted by the cast. There are many contextual layers to Dybbuks but it remained open and universal for those coming in culturally blind.

An intergenerational chorus of women singing Yiddish prayer and song is a calm and reassuring prelude to this work. They envelope the audience with sound, implying that we are as much a part of this experience as the choir.

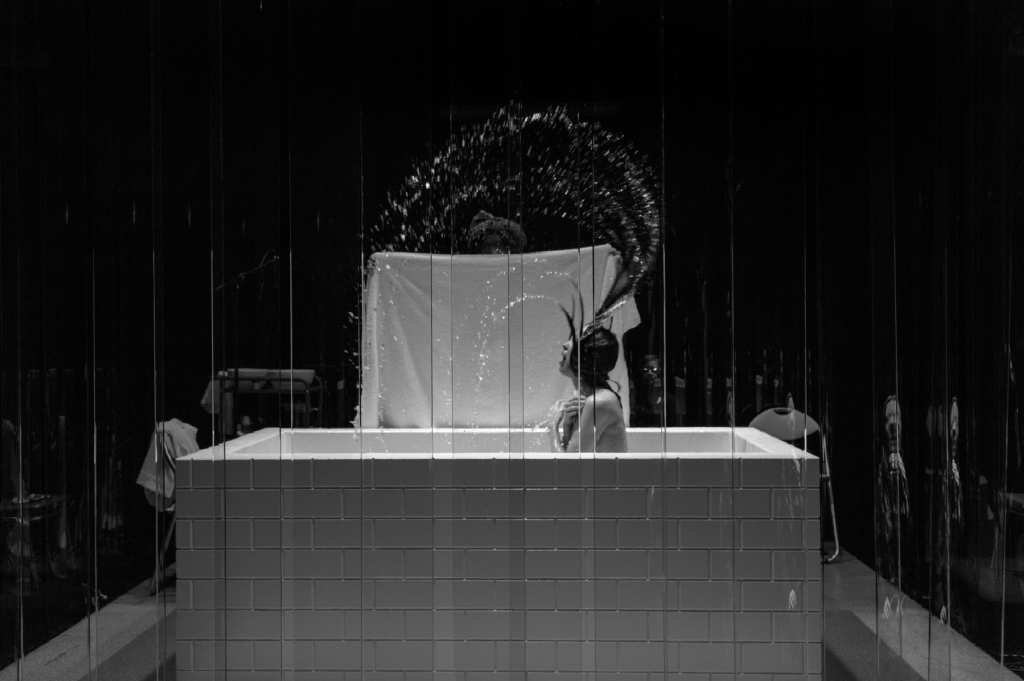

An erotically charged voice-over awakens a sexuality within us. A man and woman are bone-to-bone, so close that one merges into the other and the two become one – his spirit and her body: “This is what I was born to be.” – it is accompanied by beautifully shrouded figures under tulle. Then, we are witnesses to a ritual Mikveh cleansing in a pristine bath on stage. It is a strange and, sometimes, difficult experience. The show is completely enacted, not performed, and while we are all there watching, we often feel excluded from the event. The sound by three instrumentalists and a vocalist tends to shock and repulse, much like we are the ones ridding an inner-demon. The gurgling and screeching are almost unbearable.

Lauren Langlois is completely breath-taking and terrifying as the spirit-filled Leah. Her body is so present and tangibly open to desire and possession. It is the most effective tool for the witness to realise the presence of their own shame and sexual power, simultaneously. The culmination of her soaked convulsions is the most vivid sight of recent Melbourne stage history.

The singers are our guides through the ritual, occasionally passing through the membrane, onto the stage to become a part of it. It is very satisfying to sit with these local women and imagine their day-to-day lives, which likely do not involve such bold and daring theatrical work. In Orthodox Jewish tradition, female singing is a private act as it distracts from the males’ focus in worship and prayer. Here, it is the heart, a necessary thru-line in the soul chaos. Dybbuks was far from comfortable and sometimes lost the witnesses through unclear intentions – an ever important ingredient in any ritual.