WINDIGO

In Algonquin folklore there is a recurring figure, a cannibalistic creature, called the windigo. Windigo is monstrous greed, it’s a being overcome by a desire to possess and consume. In Canadian Oji-Cree choreographer Lara Kramer’s new work, “windigo is capitalism”. Premiering in Australia as part of Yirramboi Festival, Windigo is a sequence of possession(s) charting the devastation that capitalism wreaks upon the colonised. It’s a choreography of consumption, of the consumed, that moves from bodies, through objects and spaces subjugated to a cycle of transferred trauma.

But for a long time, the only movement in the dull white light of the Dancehouse theatre is auditory–a disembodied scratching, clicking, scraping, crackling that seems to allude to some unseen impatient activity taking place in the near-distance. Three figures–Kramer, Jassem Hindi and Peter James–sit hunched over and atop two mattresses. Their motionlessness eventually gives way to movement that mirrors the soundscape’s unease, as Hindi and James begin to pick at the mattresses with pocket knives. Both adopt awkward positions to indolently wrestle with the objects in an effort to disembowel them. James extricates and then re-attaches a tangled coil of rope to one mattress while Hindi ravenously stuffs the other’s cottony contents into his mouth. As this is unfolding, Kramer removes herself from the scene to sit beside it, turning knobs on a soundboard and watching the action develop with an intense blankness.

As the violence of this tortured autopsy escalates with the sounds of a rising ocean of static, a kettle’s boil, and Hindi tearing open a mattress to stuff it to bursting with clothes and plastic refuse and childrens’ toys, I wonder what it is that we are bearing witness to. Is it that we are watching a process of supernatural possession, or are these the abstracted effects of a very real dispossession?

A child’s voice cuts through the detritus, babbling innocently about what it means to be a princess. The child posits that princesses don’t have to worry about the effects of the elements, because princesses don’t get cold. Once again, the inability to relate the source of the voice to any body within the space places it at a kind of liminal distance, the innocence of the statement’s sentiment a fantasy or memory removed from the callous scenario being enacted in the immediate. In the physical realm, Hindi carves out a space for himself amidst the mass of junk inside the mattress and James finds a puppet that he liberates from the ephemera littering the floor. The puppet is a fluffy pink rabbit with a spring for a torso that gently bobs up and down, creating the impression that it is hopping along, though its feet never quite touch the ground. Painstakingly, James walks the effigy over the mounds of plastic and fabric dispersed through the space.

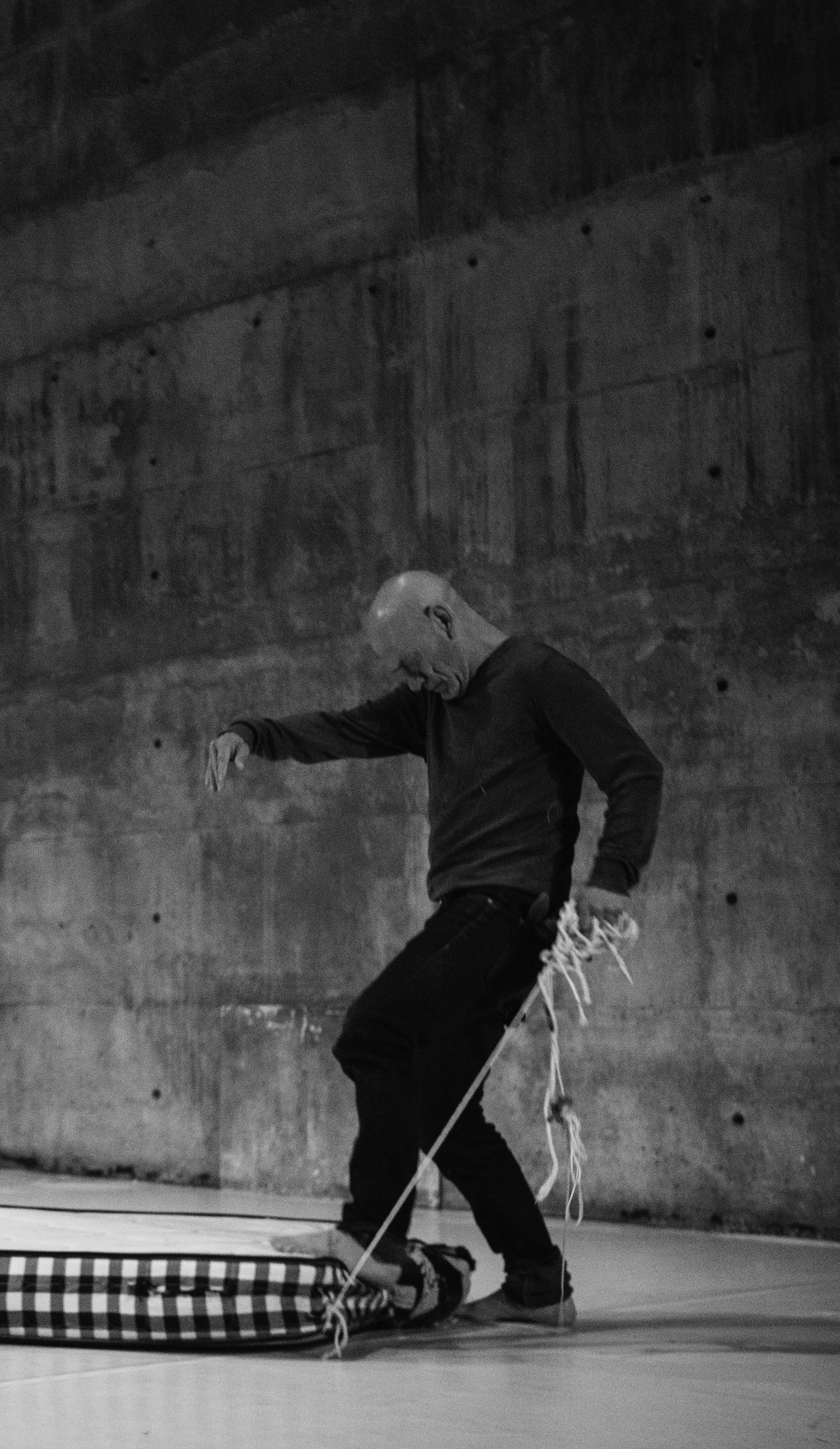

The lightness of movement here is counter-posed to the weight of the pacing. The prolonged moments of stillness and inertia interspersed throughout Windigoare heavy with a restlessness that has no direction, no outlet. Instead of finding resolve, each extended pause in the ongoing process of creation and destruction, accrues the unnamed, the inexpressible, only to explode as outburst, as excess, as violence. We see this as James breaks the hypnotic rhythm of the puppet’s bounce, transferring the movement to one of the mattresses, first through his own body by himself stomping on it, then by repeatedly picking up the unwieldy object and dropping it. It’s in these transferences that the windigo’s mark might be apparent. For here we see the characters escalate and transpose each action over and over again, as if they are attempting to bring forth some rupture in the cycle that they are suspended in. The possession then, is the hold of capitalism over the characters’ autonomy, and the subsequent dispossession is manifest in the desperate plugging of holes, the tearing of fabric, the wrapping of objects, and cutting of ties that the dancers perform to the point of exhaustion.

Through Windigo,Kramer expresses the torment wrought upon indigenous communities by colonisation, using the vocabulary of someone who has a masterful grasp on how the poetical might be drawn to devastating effect from the interplay of body, sound, space and time. For the duration of the piece, Kramer sits amongst the trash and chaos and despair, shifting sounds on her laptop screen. Of this position within the work, Kramer has said that, “It offers this idea that I’m not a character in the work, but that this is all in the umbrella of my universe.” As with the child’s voice, this sense that Kramer is somehow outside of the anguish and traumatic cycles of the piece despite being privy to them, alleviates slightly the air of hopelessness pervading the work. In this way Kramer becomes the break in the circuit that the characters are seeking, the figure on the cusp, leveraging her proximate position to hold the work ajar and exorcise the demons of the haunted world within.

The piece concludes with James’ character flicking his knife blade and seeking out adversaries amidst the scattered objects. Hindi sits, cloaked in a tinsel boa, on a stack of mattresses, mimicking the gratifying bounce of the puppet as he bobs up and down in a self-satisfied trance. Kramer silently observes all this, rising from her station to walk and crouch at the back of the space, surveying the wreckage mapped across the stage. Once darkness falls, the audience wait, unsure how to break the tension. Though Kramer opens this world of unremitting suffering to us, an exit strategy is never quite actualised. And while the lights eventually come up to applause, I can’t shake the sense that our world is still one of windigos.