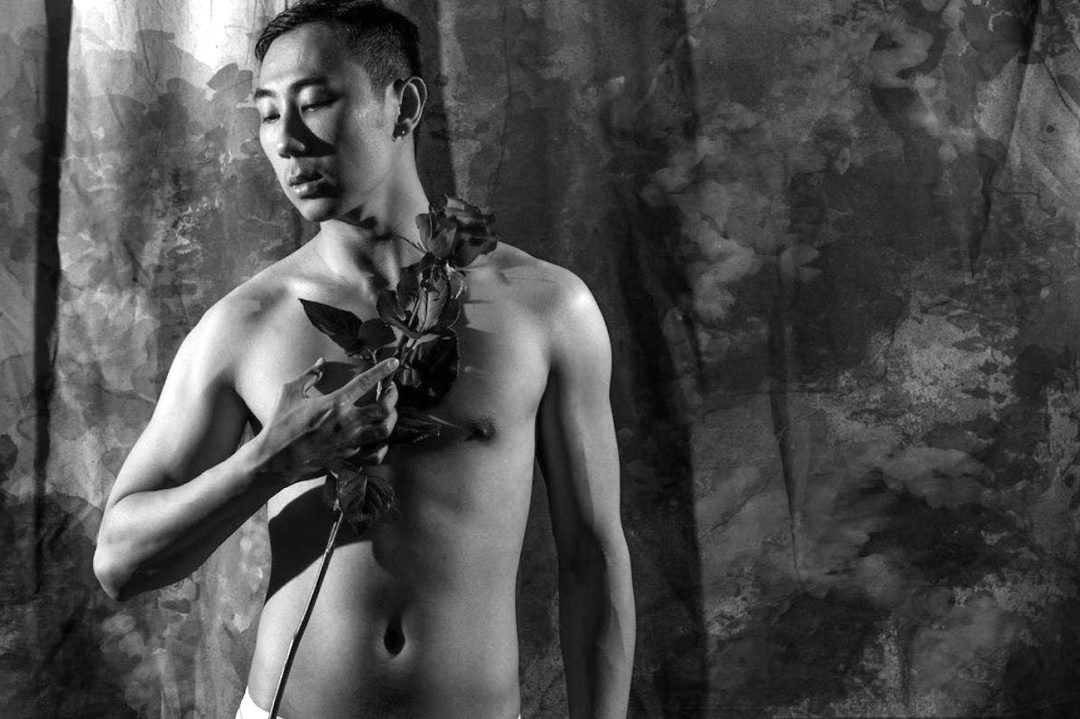

NIGHTINGALE AND THE ROSE

A lush Gothic fable, The Nightingale And The Rose, explores the beauty of love, art, creation and song from the perspective of an effervescent nightingale who hears the longing cries of a young student desperate to find a red rose to give to his sweetheart.

First penned by Oscar Wilde in 1888, it is soon to be imagined by Little Ones Theatre in what promises to be a stylised, bombastic and queer trip, an exploration into the bewitching and melancholic fairy tale. The Melbourne Critique spoke with Director Stephen Nicolazzo about the works’ contemporary relevance, the luxury of art and how to apply a cinematic treating to works of the stage.

So, what lead you to want to develop this work for the Stage, in terms of queering the classics and its relevance within contemporary society?

The Happy Prince was our first installment in our investigation of the Oscar Wilde Fairy Tales, which is much more about the concepts of compassion, self-sacrifice and looking at those kinds of moralistic values through a queer lens.

This one is more about the self-sacrifice of the artist and it’s sort of told through an almost anamorphic creature, The Nightingale, who has this idealistic notion of love that is incredibly romantic, and whom really believes in the value of love and art. But it then spirals into a dis-sectional criticism of what happens to art, what happens to love and what the material value of it is; that’s where the interest lies in developing it. As a companion piece this one is a lot darker and a lot more cynical, whereas the first was a lot lighter and a lot more about pure love.

Do you think this work is responsive to the times? You mentioned, just then, the word cynical…

I think it reflects contemporary sensibilities. For me it’s talking about how we interpret or criticize art and whether it has any value or opportunity to change the world; it’s the cynicism of it. Oscar Wilde has this grandiose and mythological story where this Nightingale is singing to the point where she creates a red rose that’s designed to give this young student an opportunity to find a lover, but this red rose then ends up discarded on the street and destroyed.

So, the contemporary relevance of that is that the things that we create, the things we make for people, can sometimes be discarded. Everything has lost charge or meaning in a world that is so fraught and there is something so tragic about that, so this story still has so much resonance in the world right now. An artist can put so much into something, and they might think that they are saying something in it, that there is real potential for change or to destabilize the universe, but for that for then to just be so easily disregard is tragic.

In saying that, do you see art and creating theatre as being a bit of a luxury these days?

Totally, I think it has sadly become somewhat of an entitled medium. The kinds of people that are going into it have the money to afford it, or the intelligence or the kind of academic ability to respond to it or engage with and I don’t know if it is reaching outside of these circles, which is really upsetting. Because there are different contexts where you can reach out to audiences that may not come from those backgrounds, but I think those are limited particularly in the independent sector. It’s hard to bring in people who need it.

I think the only solutions that I can see for this are to keep making, keep reaching out and keep trying to engage people with new ideas, or sometimes just to purely entertain them or allow them to feel something, and see if that conjurers some change or not.

So, getting back to the work, talk to us through the process of development and rehearsals.

I think with these works, because they are purely devised and as we haven’t started rehearsals yet, the next stage will centre on how the actors respond to the images and the script excerpts I have created over the last six months. What I do with it is I create a film treatment, a visual map of the story, so the actors can start to get their heads around how we are approaching the material and by the time we get to rehearsals we have a draft that we can then leap from.

The story is so rich and beautifully written that we are trying to find ways to make every detail theatrical. We are applying the same process here that we did with the Happy Prince; throwing as much as you possibly can on the floor and trying all these complex theatre techniques. Sometimes you do over-complicate things to the point where it ends up impenetrable, but then you eventually get back to the story. It’s like doing a dance around the original but then getting back to it, because you finally understand it.

Finishing off, let’s talk about the world, and what would it be like if one morning you woke and art had disappeared.

My world would look incredibly bleak. What we would stand to lose is a visceral experience that we can’t get with film, music or with visual arts. Connections between the bodies on stage and the audience would be gone and I am so driven by that. I would have no reason to get up in the morning, I would be bereft. The world would be passionless. The absence of art, I can’t even imagine it, it would be so horrific.