THE FALL

The theatre is buzzing. As I look around the seating bank, friendly faces glow with excitement. The Bla(c)k arts community have come out for this show; we smile and wave, hugs are exchanged, there is a shared hunger for this performance. Occasions like this are few and far between and already the sight of so many Bla(c)k faces in a space like this is a shift in the air.

The Fall emerged as a product of the #RhodesMustFall movement, a student revolution that began in 2015 at Cape Town University, calling for the removal of the statue of colonialist, Cecil Rhodes, and protesting against the Eurocentric, colonised nature of South African student life. This led to further, more wide -spread protest to decolonise education on a grander scale.

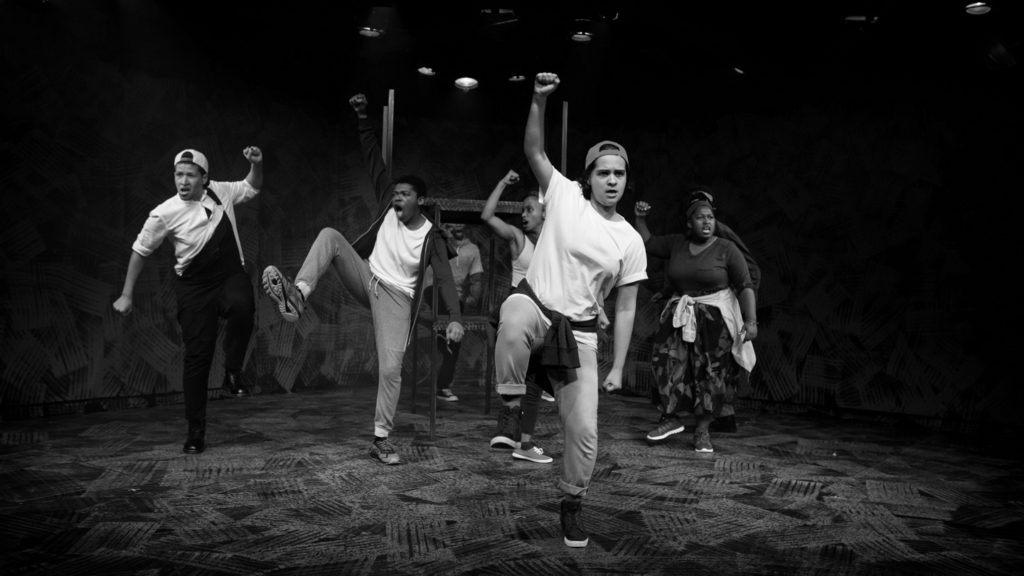

The work begins as seven performers erupt into the space, marching as a unit and singing in language with easeful, smooth harmonies. Over the course of the show, the performers activate the humbly dressed space, blank besides 3 tables, with their hilarious, passionate and powerful storytelling. We are offered uninhibited joys alongside uninhibited pains, and an honesty that leaves audiences questioning whether these are actors playing characters or people who just happen to be on stage.

It engages with themes of decolonization, institutional racism, privilege, systemic oppression, identity, gender and the power of protest; unpicked with a realistic spread of diverse and complex perspectives and experiences between the 7 voices on stage. Audiences are delivered an education, seamlessly embedded in the soul and humanity of the storytelling. Actual footage of the protests are projected onto the back wall, lending context and an overwhelming urgency to the action. The images formed on stage by the performers are simple, yet striking and direct; fists pumping, bodies marching in protest. They open their arms to us and create an environment that feels warm and homely – the comfort and strength of their bodies on stage, echoed in the audience who respond with cheers, laughs and tears.

Each character is complex and rich, a refreshing break from the two-dimensional stereotyped characters that Bla(c)k peoples are often subjected to. The knowledges and experiences, beauty, insights, ignorance and faults of the characters are played out on stage, exploring intersectionality and the multiplicity of Bla(c)k lived experiences with wit and humour. Intermittently, the characters speak and sing in languages unknown to me. Jokes are made that fly right over my head, and I can’t help smiling.

These displays are unapologetically and proudly directed to the audiences in the theatre who can understand them. An uplifting experience of resistance to Eurocentric theatre practice, tinged with a sadness that such an act is radical or exciting to begin with. As I unpick the nature of this work and its function, I am disheartened that once again the burden falls on the shoulders of the oppressed to resist and to educate – yet I am pleased with the way in which it has been done. The voices are powerful, unapologetic, and it is clear that the experience is not designed solely to be palatable and consumable for white audiences, while also quite literally providing reading material and homework for those who are under-informed.

As the work comes to a close, each character expresses their final words and potential hopes for a brighter future. I wipe tears from my eyes. A Sierra Leonean-Ghanaian brother I had met 3hrs earlier turns to me and says, ‘That was better than any movie I have ever seen,’ as the entire audience rises for a standing ovation. We filter back into the foyer to exchange hugs and looks of warmth and understanding. ‘That was so real,’ a friend says to me. We have been seen, heard, vocalised, mobilised, moved. But I can’t help but think of all the people who would benefit so greatly from exposure to this kind of black excellence. I think about the African community of Narrm, whose days would brighten to hear their languages spoken, their songs sung, see their stories reflected and their people standing with pride in a public space without the word ‘gang’ slammed across their foreheads.

The reality is that this work, which is extraordinary and rare at a time like this, can only radically impact those who are exposed to it. The demographic of the Arts Centre upholds a barrier to access; as a significantly Eurocentric/white space with expensive entry costs. While I recognise the community engagement groundwork implemented by Arts Centre such as school workshops to begin decolonising their institution, I ask arts facilitators to call into question the accessibility of their venues and therefore their messages; How can you, as the gatekeepers to cultural materials, attempt to remedy this?

The Fall reminds of the masses of work to be done, but compels and moves me to continue fighting for the lifting of oppressive forces. One particular line rings in my head as I walk home; ‘There’s only one way to evict you– that’s to do it loudly. Publicly.’