QUAKERS AND SHAKERS

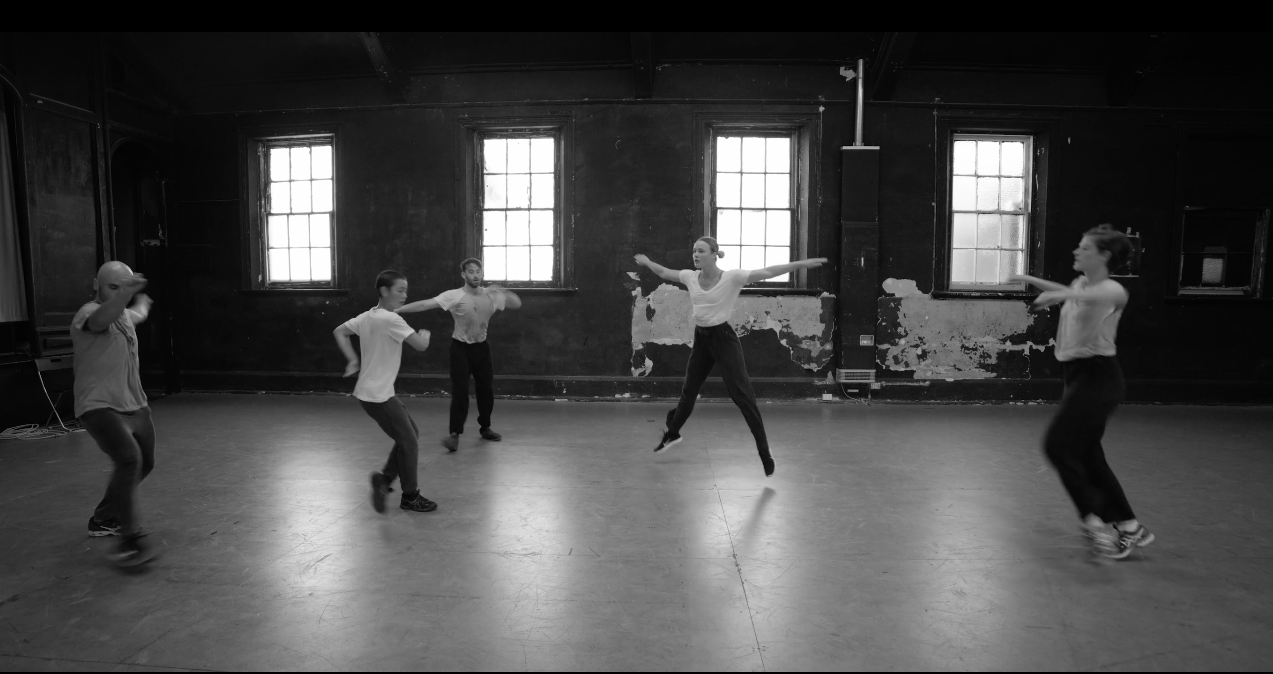

Six extraordinary dancers create an everlasting cycle of loops and oscillating ecstatic rhythms, investigating themes of permutation, transformation and the infinite. This is Ever, the latest Melbourne Festival offering by Melbourne’s very own Ballet Lab. A performance where the work of two of the most iconic 20th century chamber musicians—John Adams’ and Richard Strauss’ are reimagined through what promises to be nothing short of exhilarating and thought provoking contemporary performance. Phillip Adams, the man behind both the company and Ever met with The Melbourne Critique, in the collectives newly found home at Temperance Hall in South Melbourne.

Phillip, can you introduce us to Ever and how the works relate to your own present and personal relatives and view of the world?

In an exploration of my childhood, I’m going back to my cot. I’m not the same person. I’m not blaming technology for fucking me; there’s no blame, it’s just that we’ve evolved into a different species because of it, but I am bit frightened of what I am now because of it. I think that’s really part of my generation that are still making choreography got it call something. Actually, that’s a good place to start; let’s start with the c-word.

Has choreography become institutionalised in the way experimental is now institutionalised? As we loosely branch out into interdisciplinary practice, is that the next door way for choreographers to be available, through being available to all mediums, or are we just simply rehashing histories?

The last work Ballet Lab did for Melbourne Festival was Aviary, which was a spectacle wasn’t it? Ever is about allowing myself as a choreographer to be in that space again. It’s about giving myself permission to make dance, which was my first love and expression. In wanting to find that, how far back do you have to go? My introduction to that was in the 80s. I caught the last wave of the post-modern choreography in the day. I worked inside of that conversation for ten years, and it seemed really important. And it’s not that dance has lost some of importance, but the younger generation now, well.

Ever is about the DNA in my body at 52 to go home, to be expressed now and to not be shy about it. It has been a while since I created a dance work and fallen in love with it. I have asked a lot of questions that have come inside my body and come back out processed. Ever is about my love affair with the pure dance form.

The flip side of it is 30 years later, with our company being at its height of provocation. But today we are able to express not only in the more literal sense of choreography, but also through this visual collapse. There is a collapse in me that the audience can see in this beautiful piece of dance work, then presenting this performative work that still flies over the music with desire and devotion to art. I have become an artist. The two are like something symbiotic at 52.

But my introduction to dance in that space, architecture and time rubs up against my interests today.

Speaking of provocation, let’s talk about gender and sexuality. How are these expressed through dance?

Looking at the history of their liturgical dances, male and female, and the sexuality between them was very restrained. I just got really into that moment. So, I looked back at the early works of Martha Graham as one does. You have to go back to London. And still today she’s the biggest, most brilliant drag queen in the world. She’s the original and the best. Nothing comes close to that. She’s the shit.

Queerness seeps in subliminally. It’s been there on mini putt-putt courses. As a kid who came to see it on the Gold Coast, or the pink poodles it’s kitsch. My first introduction to camp was in Canberra. It might’ve been ’82. I’m fourteen, fifteen – anyway, I saw two shows. First one was An Evening With Quentin Crisp, and how ballsy of my parents was that! At that time, Quentin Crisp was touring with a show where he’d get you to write these questions in a book in the foyer. He’d come on stage and answer the questions. These were things like, ‘what was being gay like in Britain?’ He’d answer the questions to this super conservative Canberran audience in nineteen-fucking-whatever! I remember that I didn’t see him as a queer person, I just saw him as a person, because I had no judgement.

Looking at the history of their liturgical dances, and male and female, and the sexuality between them was very restrained. I just got really into that moment! So, I looked back at the early works of Martha Graham as one does. You have to go back to London. Even today, she’s the biggest, most brilliant drag queen in the world. She’s the original and the best. Nothing comes close to that. She’s the shit.

So, I looked more at the essence of Appalachian Spring, music of Aaron Copland and sets by Isamu Noguchi, this avant-garde time, from 1946. The set design’s minimalist porch and veranda was by Noguchi, and he designed it so the dancers couldn’t get comfortable. They were always set in the rigid-backed situation. The preacher would arrive and then salute to the sun, and then there’d be a sort of shunt to the side – the romantic, handsome farmer who wants take the girl as the space of America, the fervour of the corn fields, the eye of the plains, this puritanical preacher in this divine piece of string that would wrap around the stage on this backdrop of white.

Is there any of that campiness or queerness in Ever for Melbourne Festival?

No. So, this is the twist in the conversation that we’re going to have with my public and with my audience that are going to see this conversation from me. The last thing you would expect from Ballet Lab for me is to make a pure dance work. That’s radical! It’s very rare that I pull off a dance work these days. I think the most interesting moment is that ‘what the fuck is he going to do?’ It’s been a long time.

It’s super, super minimalist. The scores are by John Adams – of course we’re talking Shaker Loops – and Richard Strauss, Metamorphosen. Since the romanticism, high cinematic Strauss is just gut-wrenching stuff, heart-pouring strings. I looked more at the essence of Appalachian Spring, music of Aaron Copland and sets created by Isamu Noguchi in that avant-garde time, from 1946. In one, the set design’s minimalist porch and veranda was designed so that the dancers couldn’t get comfortable. They were always set in the rigid-backed situation. The preacher would arrive and then salute to the sun, and then there’d be a sort of shunt to the side – the romantic, handsome farmer who wants take the girl as the space of America, the fervour of the corn fields, the eye of the plains, this puritanical preacher.

How does dance match that, though?

You’ve asked the best question. I could not compete with the score. I gave in. I just said I’d rather the audience just listen to the music than choreograph this. I would not even attempt to do it. So we have this romanticism and minimalism, so they’re set like fifteen years apart, and written fifty years apart. What flies over the top of it is my love of Modernism and Post-Modernity and art. So, they don’t bleed. I see them as one topic of conversation for the meaning to arrest choreographic exploration and visual experience.

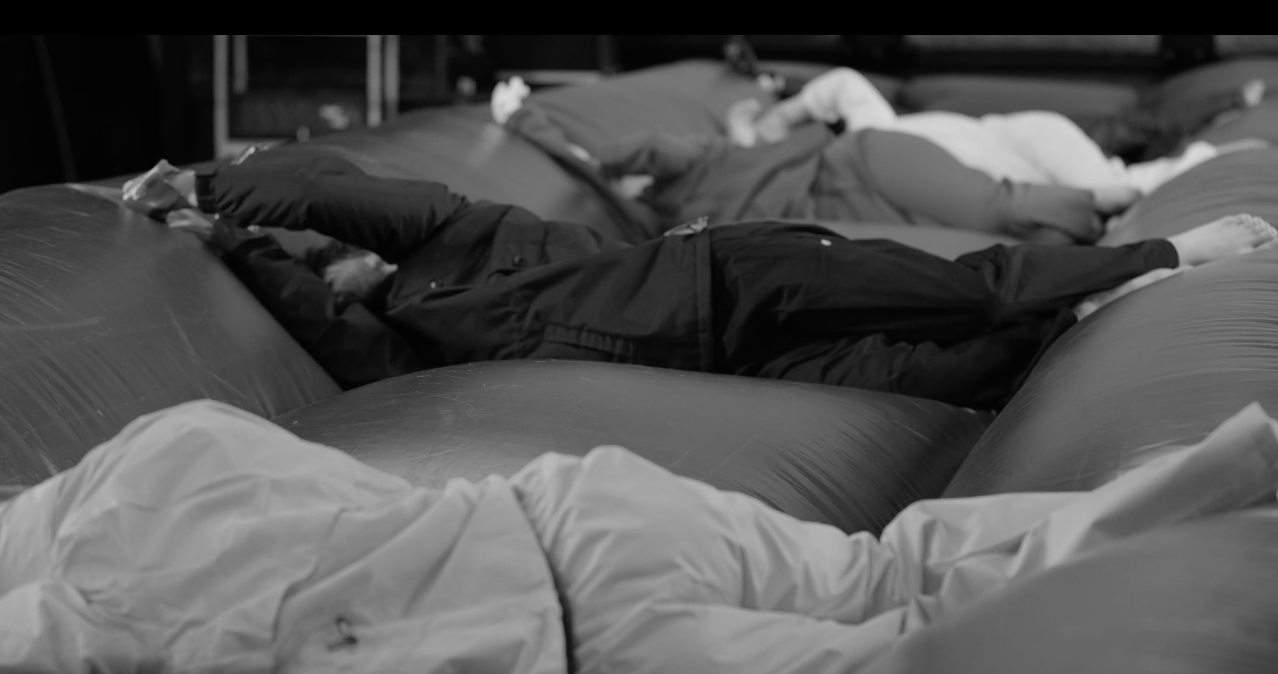

I want the audience to be equal listener and watcher. That’s the hardest thing to do. In all of my attempts, every single one of them, I failed to respond to the Richard Strauss. But I just keep going until I have something worth talking about. So, for half a year, I just rolled to the music. I’m talking the most basic, bad contact improvisation you can ever do with another person in your embrace – just roll for hours, weeks, days.

I showed it, and people were like, ‘that’s the worst thing I’ve ever seen.’ This is great, let’s keep going. But I knew the answer would come! It’s this trauma. If you’ve never met somebody and you’re asked to roll with them, it’s like, well, do I do it? And then after one hour you’re like, well, our bodies are sweaty together and you’re having this exchange and it might become really emotional. There might be tears.

And your breathing comes in-sync?

Yes. Or, is there a stop? And we would do this and we’d invite people in off the street. You would do anything. You’d do it in public – which we did. Until I let it go. I just collapsed and just let the music allow me to continue to explore. The idea of the first work is this minimalist, absolute. Akira Isogawa designed the most absolute fuck-off costumes in the world. They are pure Quaker and Shaker, Amish Zen.

So how does it get pulled together?

Shaker Loops, if you look at the scores, is a mockery of the Quakers and the Shakers and they were sort of frowned upon. They were a little bit cultish; they would stand in circles and shake, and they were this rejection against society and their whole conversation around purity. They were pretty out there, even though they were the most conservative movement of the Amish invasion of the spiritual father that inherited America during the 1800s.

So, I’ve gone home, I’ve lassoed Arthur into my world because Shaker Loop by John Adams is actually a response to Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring. So I’ve tried to take that conversation and explore the collision of all of that into cycle that continues as one expression of music. I ask my audience to be silent when they enter the room, just observe the silence. You are the frame. I’m asking you to watch and listen. Be observant to pure choreography. Be the judge.

At a point in the second part of the program, all physical presence, knowing, must evaporate and can only be expressed through paint. So I’ve been painting. Painting with my desire to replicate history and doing a pretty bad job of it. I hung a may pole in then middle of the space downstairs and I made one of the most complex and interesting choreographies I’ve ever made. The dancers were in love, but then I cut it as soon as it became too beautiful. I understand I’ve made this because I need to make it cinematic. I need to do this myself. I need to paint this maypole with my paints, and I’ll squeeze the paint, I’ll tie it in knots and allow myself to be the artist who is the may pole who is the expression.

My response Richard Strauss’ Metamorphosen is one drop of paint. It just starts in the film, and you watch it for a very long time, and you start to listen. You start to think of the trauma of that one brushstroke. My process now as an artist is that you come to see Ever, which is pure Phillip Adams choreography, sort of rehashing the 80s. Then you just sort of drift away into what I am making today as a response. But I see it as one condition of my brushstroke now as an artist making dance and visual and paint and things.

I’m going to finish with one last question and one big question: the future of dance and the future of art.

There’s certainly a bigger conversation. My prediction is that the planet, as you said, has this neon around it that says ‘fucked.’ It’s like a big neon sign, a big artwork. Inside of that, the commercial viability of culture has never been more relevant in politics and in art. It’s commercial. It feels like everything has become generic. A curtain dropped, and we became fearful again of something that just almost came without warning. Like a tsunami of fear hit the planet.

Is it that we over-populated? Is it that we got too close to the borders of religious fervour between the rub of cultures? Then, to look at the bigger conversation of the future or the hope for people like you or me and the man that made these works in this room, I think that it’s our ignorance as artists to what’s beyond the political fucked neon of the world is that we continue nevertheless. Nevertheless, I will go on. Yet, in that curtain I as talking about, like that intermission moment-

I feel like the world is in an intermission. I feel like we’re in the intermission phase of a soap opera. The curtains come down on Act One and it’s not looked good, but I feel like Act Two is really, really fabulous. I feel like the positive light is a rebellion in a cinematic way. As much as I can be clichéd, the rebellion is making its plan. I think that artists are making plans underground, and underground is where it’s at.

I opened the Melbourne Festival program and I’m really excited, but I’m also going, ‘where is the disruptive culture to come against the spectacle of the European expression of bourgeoisie theatre?’ Melbourne has that in its path and in its grip for a long time. We’ve got that card in our deck.